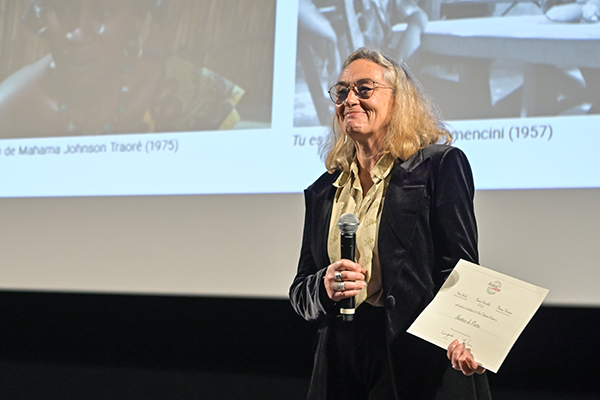

Béatrice de Pastre

« The restored œuvre must be the one that audiences saw in theatres. »

PostED ON 15.10.2025

Béatrice de Pastre, Director of Collections at the National Centre for Cinema and the Moving Image (CNC), has been awarded the 2025 Fabienne Vonier Prize, which recognises the work of a woman in the film industry every year. She talks to us about her approach to film restoration, her view of heritage classics, and her upcoming projects.

© Jean-Luc Mège Photography

You like to take care of the most fragile films. Can you give us a concrete example that represents your work?

René Clément's very first film, Evasion (1935), was screened in a restored version at the festival just before I received this award. It’s a previously unseen seven-minute short that is part of the director's aesthetic journey. Restoring it gives us a better understanding of his path. The role of the CNC is to take an interest in these more elusive objects too. However, there’s no financial advantage: this film can’t be shown in cinemas. In this case, it was a first film that was screened, but it could also have been commercials, trailers, anonymous documentaries... All these things together make up our film heritage. It's not just about masterpieces!

What can the cinema of the past teach cinema of today and younger audiences?

René Clément was 22 when he made the film Evasion. It is interesting to see how a director tackled a subject and to think about how he overcame a whole array of technical difficulties to obtain the images he wanted, even though with today's technology, we could achieve what he was unable to do at the time. For example, the prison bars are actually painted broomsticks. That's also what cinema is all about: knowing how to adapt, tinker, and make it so the audience is none the wiser. These are elements that can be inspiring for young artists today: discovering sensitive emotional worlds, regardless of generation. Being confronted with emotions is important.

When restoring a film, why is it important to respect the original work?

A film is the result of the convergence of three entities: a director, the director's culture and technology. If, for example, a film from the 1930s is restored, it will, in a sense, be cut off from its origins and will no longer be available to future generations. Today, we are fortunate to still have access to film, but in 50 or 60 years, this knowledge will disappear, and we’ll no longer be able to recognise what film belongs to which era. So it’s important to leave visible traces of what characterises the era of the film. For example, it is sometimes interesting to leave the ‘camera hairs’, that can be seen in the image. Technicians did not always have time to clean the camera. It's part of the history of filming!

In your opinion, why is it beneficial for the director of photography to be involved in the restoration of a film?

It's very good if they can supervise the colour grading of a restoration, for instance. That's what's extraordinary about these technicians: they still have the fire in their eyes. They are a tremendous source of information. For some directors, it's also an opportunity to sometimes make the work they weren't able to produce before, but that can become problematic. So you have to strike a balance between receiving this essential information and always respecting the original œuvre. Our guiding principle at the CNC is that the restored œuvre must be the one that audiences saw in theatres.

Is there a search for specific materials for restoration?

Yes, we also have to identify the historical facts of the films, because sometimes we find the negatives as they were printed, with no further information. The negatives may have been cut for censorship reasons or by accident, and we have to reconstruct the original work. Sometimes we restore a film from a print. For example, we restored Cleopatra by Henri Andréani and Ferdinand Zecca (1910) from a print that came from Mexico. It was twice as long as what was listed in the Pathé catalogues because many of the shots were not part of the original film at all. So we removed the unrelated material. But it's fascinating, because it tells us something about film allotment and how films were distributed at a given time.

Is it true that a large swath of silent films, around 60 to 70%, have been completely lost?

It depends on the period and the films. It’s true that there are many gaps in the period 1896-1905. But there are catalogues that we’ve been able to reconstruct, such as the Gaumont catalogue. Certain small production companies suffered greatly, sometimes due to accidental fires caused by the flammability of the film stock, other times, due to choices of the era: public burnings were organised to destroy prints, simply to make room for new films.

Incidentally, is film restoration dangerous?

Yes, that's why the CNC has set up a facility to store all these items in the most secure way possible. We are fortunate in France to have made this cultural policy choice in the 1980s and 1990s, which has enabled us to carry out restorations and preserve these original elements. It was not the case in Germany or other northern European countries, for example.

This year we celebrate the 130th anniversary of the filming of the first film in cinema history. Could you say a few words about your work restoring Lumière films with the Institut Lumière?

Working with a Lumière negative is a wonderful adventure. It should be emphasised that these films are of very high quality and inspire wonder. They bear witness to a milestone in History, beyond the History of cinema. The Lumière catalogue includes science fiction films, camera movements, close-ups, and so on. It has everything! These films also give us a glimpse of society at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, which is quite moving.

Concurrently, we are also conducting a fascinating investigation into the identification of filming locations. There are still some unknowns about certain films, such as Toboggan d'eau, which features a roller coaster in the water. On one of them, a leader (a piece of film attached to the beginning or end of a reel to help start the projector -editor’s note) was written in Chinese. This is very mysterious since no Lumière films were shot in China. These kinds of little mysteries are exciting!

Reconstructing the Lumière catalogue is not just a matter of looking at the 1,408 films contained, but also realising that there were sometimes several takes, for commercial reasons. We can then see how the Lumière company envisaged the dissemination of its films and how they circulated from distributor to distributor.

You were Director of the Robert Lynen Film Library in Paris from 1991 to 2006. You accomplished a tremendous amount of work there. Could you tell us about it?

When you're in a small organisation like that, you find yourself having to make an inventory of the collections. The circulation of images was invented in the 1910s, and this film library was originally created (in 1925) to enable teaching through images. Every day, operators would go to schools to show films to pupils.

I conducted an investigation to find out why a ‘talkie’ had become a ‘silent film’. It turns out that the film library purchased films with a ‘blacked-out’ soundtrack, as it’s called, so that teachers could comment on the film to their classes. We had to find ways to show these films again to schoolchildren in Paris in the 1990s and 2000s. It is interesting to see how these science films from the 1910s could still be interesting to children in Paris in 2000. It was a wonderful challenge.

What is your view on the success of classic cinema today, which has become quite ‘commonplace’ with screenings at the Institut Lumière, for example?

For some who have been working in this field for years, it's akin to the spirit of film clubs. There has never been a total separation between the cinema of the past and that of today. People want to rediscover works of yesteryear. What's more, the films are magnificent because they have been restored, so the viewer's enjoyment is multiplied.

Wouldn't it be better to show, at times, an imperfect, worn film, to preserve the enjoyment of rediscovering an œuvre in these conditions?

Yes, it's important to maintain this connection, to show that it exists. We must also bear in mind that not everything can be restored, it involves tremendous costs. These are objects that film libraries try to showcase. My colleague Franck Lubet, at the Toulouse film library, regularly organises surprise screenings, as is the case here at the Institut Lumière. The choice is random because the print has to be suitable for projection. These screenings are very popular because there is the pleasure of discovering the work and of the object itself, which sometimes contains scratches, but it’s accompanied by its authenticity and incredible charm.

Do you agree that the notion of ‘heritage cinema’ is undergoing a transformation?

It's obvious: heritage becomes increasingly important as time goes by. Today, as part of our digitisation initiative, we consider films that were released in cinemas before 31 December 2009, so heritage officially goes back to that date, which corresponds to more than 110 years of film production.

In a decade, the age limit will be brought forward. There will be technological issues when it comes to shooting films digitally: software will have to be invented to limit special effects and any other elements used to create digital images. My successors will undoubtedly have a lot of work to do in this area!

You are also a teacher and you have published the book Revoir le cinéma muet en France (1908-1919) (‘Revisiting Silent Film in France, 1908-1919’). Could you elaborate on that?

This project, led by Laurent Véray, professor at Paris 3 Sorbonne Nouvelle University, has been a long journey. The French Film Library, the ECPAD (French Defence Audiovisual Production and Communication Agency), the CNC, along with academic figures, contributed to this book. We all worked together, the researchers and the institutions, to describe this period from 1908 to 1919. It was considered disastrous because of WWI, but it’s also very interesting in terms of cinema, given that the industry adapted to the wartime conditions. In 1918, how could French cinema resist the massive influx of American films, and how did it reinvent itself during that period?

In the context of this book, we also organised identical reconstructions of screenings, using programmes from 1908 and 1919, to show what it was like to go to the cinema at that time, and to compare cinema in 1908 with 1919. The screenings were often divided into two or three parts, and always featured an orchestra. We tried to bring this history back to the spotlight and share these sometimes-surprising objects with the public. Each screening was a real delight for everyone!

Is there a legendary project that you would like to prioritise?

I have many plans with my colleagues at the French Film Library. As with the Institut Lumière for Lumière films, we’re going to work on Travail, a film by Henri Pouctal (1920) adapted from the book by Émile Zola. This absolutely astonishing epic film was shot partially in northern France. It's an exciting undertaking.

There is also a project based on the film Lest We Forget (1918) starring Léonce Perret during his American period, which I had already worked on in the past. The digital work we had done has disappeared (that's the charm of digital!), so we have to start over again. It's a story about a shipwreck in the Atlantic during WWI.

Let's talk about L'Aventure cinématographique de La Croisière jaune, (‘The Cinematic Adventure of The Yellow Journey’), another book you contributed to, based on André Sauvage's documentary La Croisière jaune (‘The Yellow Journey’, 1934). Could you tell us a little about it?

It took ten years! First, Léon Poirier restored the film using André Sauvage's footage. The film was distributed to cinemas and screened at the Sorbonne. André Sauvage had deposited images with the CNC that he didn’t have at the time he was taken off the project. We tried to reconstruct the entire journey using images that were not in Léon Poirier's initial montage. The film was meant to become a technological adventure in sound, but the very fragile material couldn’t withstand the desert dust well, so there’s very little live sound recorded, and these images bear witness to all these difficulties...

At the same time, Agnès Sauvage (André Sauvage's daughter) gave me all the letters her father had sent to his wife. It represents a kind of logbook that recounts the filming process. One follows the initial enthusiasm, then challenges begin to emerge. André Sauvage was disappointed that he couldn’t execute his artistic vision. This project was a journey for me too.

Fanny Bellocq