Conversation

‘The important thing is to

show reality in cinema.’

Posted on 19.10.2025

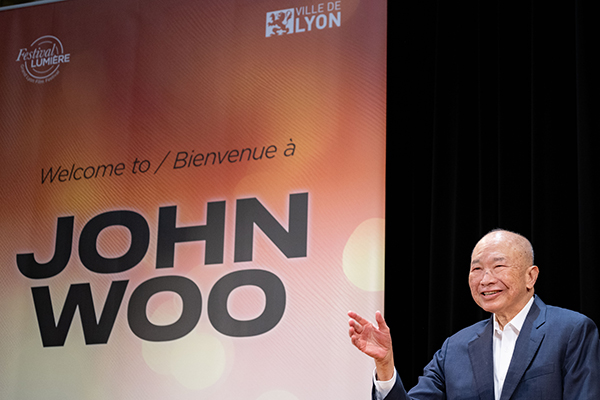

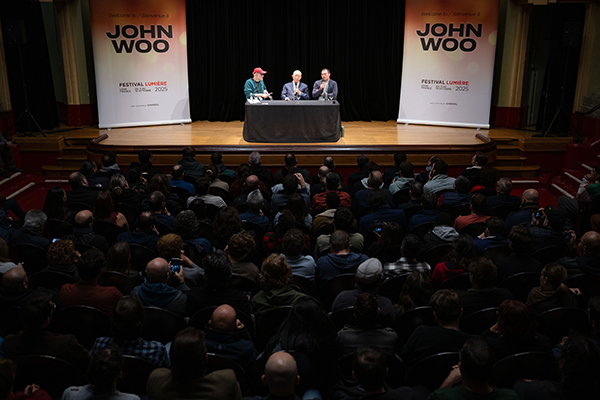

The 79-year-old Chinese director, screenwriter and producer is one of the guests of honour at the Lumière film festival. Considered the master of Hong Kong action films, John Woo, who rarely makes public appearances, came to meet the Lyon audience, who welcomed him with a sustained ovation.

© Loic Benoit

Your career as a director got off to a difficult start. Before the success of your film A Better Tomorrow (1986), can you tell us about your early days as a filmmaker?

I didn't study film when I was young, so I used to go to libraries to borrow books on the topic. That's how I got by, and that's what provided my education about cinema. It's important to note that in the 1950s and 1960s in Hong Kong, when you went to the cinema, you could see films shot in Mandarin, but it was a cultural desert: there wasn't much of a choice. It was in the 1960s and 1970s that we started to see other films. Watching works of the French New Wave was a real revolution. My cinematic youth began with French films. François Truffaut's Day for Night (La Nuit Américaine, 1973) was one of the first films that had a profound impact on me.

I also think of François Truffaut's other films, as well as those of Jean-Luc Godard and Jacques Demy, in particular The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (Les Parapluies de Cherbourg, 1964)... I love the romanticism and love that are imbued in these movies. For example, the love that emanates from a leaf falling from a tree. All this made an impression on me in terms of the romanticism that can emerge from it. You can find this by watching my films.

At the beginning of your career as a filmmaker, cinema at the time was dominated by martial arts works and comedies. You said you felt lonely then because you couldn't do exactly what you wanted to do. Could you elaborate?

At the time, it was very difficult to make movies in Hong Kong. The film industry was monopolised by certain families, and if you weren't part of those families, it was even more difficult to make films. Back then, you had to be 60 or 65 years old to start making films. If you started at 45, you were considered a very young director! We very rarely went to film schools; we learned from established directors, through a master-apprentice relationship.

I probably became a director by accident. I started as an assistant director because a producer wanted to flirt with one of the big Hong Kong stars of the era. That's how I ended up being given my first film at the age of 26, just to allow that producer to get close to the actress in question! In the end, I became a director, but the producer didn't achieve his goal because the actress was difficult (laughs)!

We had extremely limited resources, thus we had equipment that didn't let us record sound properly. For most of the films we shot, we had to film the scene first and add the sound later, because otherwise the noise of the engines was audible.

But ‘thanks’ to this lack of equipment, I learned one crucial point: the first thing you need as a director is a good set of eyes - a good eye for detail. At the time, we only had two or three lenses to shoot with, maybe one more for close-ups, but that was it. For instance, there was no monitor to review the results and adjust. That taught me to develop a keen eye and choose shots and images based on my impression, not just on the images I could see on the monitor.

At the same time, a ‘new Chinese wave’ movement was gaining momentum. You developed a great friendship with director Tsui Hark. How did this encounter come about?

It was around 1975. Many directors had returned to Hong Kong from abroad, mostly from France and Canada. It was a time when I needed friends, I wanted to meet new people. Tsui Hark and I got to know each other and decided we wanted to change Hong Kong cinema, inspired by the French New Wave, but the studios weren't very open to that notion at the time. Their main interest was making money, not revolutionising cinema.

These young directors were primarily shooting television series and had very little room for cinema. I remember seeing a scene in an episode of a series that struck me as violent, with a sword and blood dripping. That shot made me want to know who the director behind the scene was, because I found he had a cinematic approach, not just a TV series style. It was Tsui Hark, and I immediately wanted to meet him. For a year, I tried to recommend this director, even though I only knew his name. But nobody wanted to hear about him at the time.

The first time I saw him, he was with his then-girlfriend (who later became his wife). He was wearing a coat full of holes, had a beard and very long hair, which gave him the look of a vagabond and an artist, and as soon as we met, there was a great connection between us. I told him, 'You're so much of an artist. Maybe you should make mainstream films at first, to make money, and then you can do whatever you want. His girlfriend advised him not to listen to me: she thought I was talking nonsense!’

Tsui Hark and I often met up in a bar in Hong Kong to share a beer together. It was a place with a magnificent view overlooking the harbour. And there, we decided that we were both going to improve Hong Kong films. We made this promise to each other for two years, and I took advantage of the creation of a new studio that was gaining some renown at the time to recommend Tsui Hark. That's how his career in cinema got started!

It was the dawn of a new era for Hong Kong cinema, with new ideas and fresh approaches. It inspired other directors to do the same. I was happy for my friend. And plus, he was also a big fan of French films!

The importance of this friendship, and even the love we had for each other, is fundamental to the creation of Hong Kong cinema. Tsui Hark is more talented than I am! He himself helped other directors with editing, production and other aspects, and I’m very proud to have contributed to building this new hope for Hong Kong.

In A Better Tomorrow, you blend Chinese and Japanese cinema with Western influences. What inspired this project?

In this film, beyond the various influences of Chinese and European cinema, the most important thing for me was the feeling I wanted to portray. In fact, when Tsui Hark began to become popular and enjoy success, I became much less visible. I was even despised by the film industry. Some people wanted me to retire! Tsui Hark himself found it difficult to be marginalised to such an extent. He said that I needed help in return, and that's how he encouraged me to make A Better Tomorrow.

Initially, the script I had written wasn't very good. Tsui Hark pushed me to rewrite the script and the dialogue, recommending that I dig deep within myself. He encouraged me to 'write myself' into the film, to convey the friendship between the two main characters, which represents our friendship, and to make it the central theme of the film. That's what counts in cinema: having a friend who can support you and encourage you, so that you can achieve something successful, beyond technicalities.

© Loic Benoit

Emotions emanate from your œuvre largely due to your direction of your actors. In A Better Tomorrow, you bring together several generations of artists. How did you work with this unusual setup?

I sometimes face a major problem: I can't always find the words, the language to express to my actors what I expect from them. Even before writing the script, I meet with them and talk to them, because I want to understand their perspectives on life, and, based on how they love and their way of expressing themselves, imagine the best angle. That's where I start when writing the script. I try to find what lies deep within myself. So when the actors receive the script, they immediately understand what I've written and what I want to attain.

This is something I've greatly borrowed from François Truffaut's films: I sensed all the love he had for his actors. I feel the same way about my actors and actresses, and you can tell on screen! One of my actors once said to me, ‘What you wrote in the script is something I've already said in real life!’

You once made one of your actors think he was participating in a rehearsal, but in fact you left the camera rolling to make it look more real. Tell us about that experiment...

You must understand that Ti Lung had been a big star ten years earlier, but he was in decline at the time of filming. When Tsui Hark went to find him, his goal was to portray this decline in his career on screen. The actor was suffering from depression and alcoholism, and also had family problems, which was very visible during filming. We wanted characters who could express their own lives and experiences, which is what we wanted from Ti Lung: to have him play both his past and his present. Sometimes he didn't quite understand what we were expecting from him. So we ended up with expressions that were more awkward or depressed than he would have wanted.

Regarding Chow Yun-fat: when you were filming A Better Tomorrow, did you realise at the time that you’d go on to make five films with him and that he’d become your alter ego?

I was already somewhat familiar with Chow Yun-fat's acting before he starred in A Better Tomorrow. I loved his good looks and charisma, which reminded me of my idol Alain Delon. I saw something in his eyes, so I tried to capture everything I saw in him, not only in his gaze, but also in his demeanour and the way he dressed. What I liked about him was that he acted in a natural, authentic way. I projected myself onto him a little: I wanted him to portray what I couldn't. He himself was very keen on being in more scenes, so he could demonstrate his full potential. So I ended up fleshing out the character a little more, by adding elements, for example.

[SPOILER ALERT] Did you regret killing off the character he played at the end of the film?

Not really, because at the time, I was a fan of old Chinese tales, some of them very ancient, which told stories of assassins and warriors, where the hero often died at the end, for example as a sacrifice. That doesn't bother me, because sometimes by killing off one character, you can save another. That's the Chinese martial spirit that I wanted to convey.

© Loic Benoit

You also don’t hesitate to show your male characters cry, which was quite unusual at the time. Bruce Lee never cried, for example.

The standard in many American films at the time was that male heroes never cried on camera. They would usually turn their backs to start crying, then turn back to face the camera only once the tears had started flowing. There was a kind of unspoken rule in cinema at the time due to the fact that there were two types of audiences: action movie fans, and arthouse film fans. The former didn't want to see tears, the latter did... I needed to show the characters' emotions: anger, sadness... It was quite difficult to do that at the time with American standards.

I will use the example of Face/Off, where the character played by Nicolas Cage wants to bring back memories for his partner. He was going to remind her of an experience with a dentist who had pulled out the wrong tooth: it was written in the script. I said to him, ‘When you remind your girlfriend of this memory (a funny but nevertheless moving scene), could you try shedding a few tears?’ Nicolas Cage asked me, ‘Are you sure? Because usually the studios request that we not do that.’ I replied, ‘Of course, you should, if that's how you feel!’ You also have to make the audience feel those emotions. So I kept both versions: the one where he cried a bit and the one where he didn't cry. I showed them to him and asked him which one he preferred. He replied that the one where he cried was better after all.

You recently made a film, Silent Night (2023), in which the character cannot speak. Is this to remind us that in Hong Kong, sound is not recorded live?

It’s more about the experience I described earlier, where sound had to be added in post-production, sometimes the dialogue between characters even had to be dubbed. I was inspired by the œuvre of Jean-Pierre Melville, thinking it was a nice way to pay tribute to him. In his films, the actors don't need a lot of dialogue, just a good atmosphere. Sometimes they express more emotion with less dialogue, or with even a total absence of dialogue.

Music plays an important role in your films: even the assassin in The Killer plays the harmonica. Are you a musician?

I love music, but no, I'm not a musician. Yet it's true that music is important, and I try to make it correspond to what I see. It's almost instinctive. It's not uncommon, especially when I'm making my action films, for me to put on headphones and listen to music. It helps me to bring dynamism to the scenes, to coordinate the rhythm of the action with that of the music. Of course, I also listen to music when I write - often classical music, but also soundtracks from other films, especially by French composers, or composed by Ennio Morricone, so a lot of European film soundtracks.

You have directed many works on war, and they are often darker than your action pictures. How has war influenced you?

I myself have seen many war films. They allow us to explore all kinds of human emotions, such as sacrifice, the struggle for survival, or even the conflict between sacrificing oneself for a cause and the desire to survive... I want to continue making war films, it's something I'm passionate about, but it often requires a very big budget.

Are there any personal family stories about the war that have also had an impact on you?

I was born in 1946, after WWII. My father served in the army. My family told me a lot about the war and how brutal it was, so it's something that stayed with me for a long time. Sometimes I try to convey that on screen. I like the idea of wanting to sacrifice yourself for your family, for your friends or for love, to fight for it and see it through to the end. It interests me, and I have a lot of respect for soldiers who fight for peace.

You show a great degree of violence in your films, even though you supposedly hate it. Why is that?

There is a Chinese adage that says, ‘To combat violence, sometimes you need more violence.’ In other words, to denounce violence, to condemn it, sometimes you need to go to more extreme lengths. I want to show that the traditional Chinese spirit is one of sacrifice: it involves fighting injustice through cruelty or violence. I like to show how one can go to the limit, through something more intense. It’s a political and social statement that I make by using violence in my films.

Your creative energy initially emerged from having to fight against people who did not understand your approach or your art. Has anything changed now that you are considered a cinema master? Do you feel more like a general on the battlefield or an orchestra conductor?

I’ve never really seen my career as a kind of struggle or conflict to defend my ideas. Not a director or conductor. What interests me most is making friends through my films, expressions of love and kindness. I feel increasingly relieved and free because I’ve managed to create relationships through my films, and ultimately, that’s enough for me. What has changed personally, is that I probably need less violence and action to express the humanity I want to convey. So maybe I’m becoming less and less of an action film director and finding other ways to express myself.

Perhaps you’ve noticed that I have adapted very few novels or other stories for my works. Most of my films are based on life, on things I have seen and heard around me, stories of friendship and family. The important thing is to show reality in cinema.

Reported by Fanny Bellocq