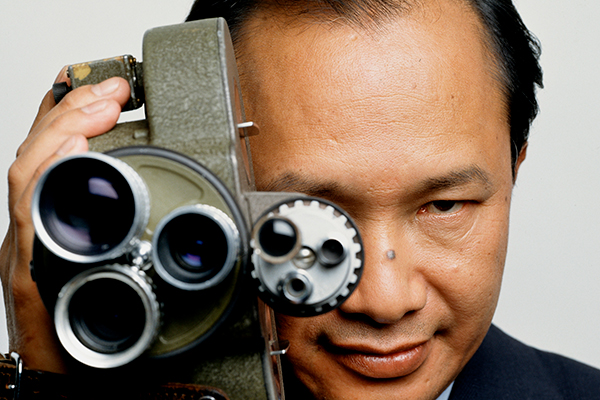

Guest of honour

John Woo, so french

Posted on 19.10.2025

Since his debut in 1974, the Hong Kong filmmaker has distinguished himself through his ability to elevate a gunfight into a poetic experience.

© DR

A cornerstone of the Hong Kong New Wave, China-born John Woo (1946), began making kung fu films in rapid succession from 1974 onwards – he directed Jackie Chan in his debut film, The Hand Of Death – before deploying his unique aesthetic with two works: A Better Tomorrow (1986) and exemplified by The Killer (1989), which combines introspection, ethical dilemmas and ballistic virtuosity to such an extreme degree, that it brought ‘fanatics’ like him to their knees, including Martin Scorsese, Oliver Stone, and Quentin Tarantino, the first figures to confess their admiration, blown away by the way Woo elevated the conventions of the thriller to universal heights, enriching them with a sensitive touch.

A film buff before becoming a filmmaker, Woo, like Scorsese, grew up on pre-war cinema (and beyond). Two of his go-to films are Jean-Pierre Melville's Le Samouraï and Jacques Demy's The Young Girls of Rochefort, never failing to mention the emotional connection he has with these French classics: ‘I've always thought I had a lot in common with Jean-Pierre Melville. He's a silent tiger, a hopeless romantic. Ideas of justice and friendship eclipse all else. His characters have helped me overcome many trials and tribulations. He's a master.’ According to Woo, Melville ‘understood Chinese philosophy better than some of the country’s own filmmakers... His characters abide by a code of honour akin to chivalry’. Woo’s genuine melancholy for traditional Chinese values is conveyed by the virtuousness exhibited by his solitary heroes in their quest for redemption, even when they feel haunted by their demons and destiny. This is certainly the case of the main character in The Killer, inspired by Jef Costello (incarnated by Alain Delon) in Le Samouraï.

© DR

The Killer (1994)

The more nuanced connection with Demy is apparent in Woo's attention to the musicality of movement, the stylisation of urban settings and the depiction of romantic feelings. Woo often refers to the influence that the melancholy and visual elegance of Jacquot de Nantes had on him: ‘Jacques Demy's films show that beauty and sadness can be combined in the same shot.’

This subtle dialogue with French cinema endows most of his great films with a unique aura. Woo's action always combines moral tension with refined mise en scène. His blockbusters are not interchangeable. Even in directing the second instalment of Mission: Impossible, John Woo manages to be... John Woo, insofar as the gesture and the gaze remain the emotional centre of gravity of the plot, behind the pure action. The invitation to Lyon for the director of Face/Off is thus a tribute to this rich, whirlwind cinema, which John Woo fuels with that ‘tragic sense of life’ spoken of by the philosopher Miguel de Unamuno — and with a profound sense of heroism, when he says, ‘A bullet can sometimes mean a second chance — or the end of everything’.

Carlos Gomez

Master class

An exceptional encounter with John Woo

Sunday, 19 October at 10.45 am in the superb theatre Molière of the Palais Bondy

The programme

Bullet in the Head by John Woo (Die xue jie tou, 1990, 2h11, Prohibited for ages -16)

Pathé Bellecour Sun. 19 at 3 pm